For as long as there’s been a “retro gaming” subculture in the US, the canon has been fairly limited. Mainly because of the second big gaming boom launched by Nintendo and expanded on by Sega in the late 1980s, legacy series from those two companies, like The Legend of Zelda and Sonic the Hedgehog, have dominated the landscape. This has changed a little over the past decade, as YouTube and Twitch have allowed for the dissemination of “hidden gems,” and the definition of “retro” has broadened with the march of time — the PlayStation celebrates its 30th birthday this year, the Nintendo DS its 20th. (Feel old yet?)

But for the most part, retro gaming in the English-speaking world is still largely focused on consoles. There are good reasons for this — it’s often much easier to emulate console titles than to make older PC games run on modern operating systems, despite the ongoing work of preservationists. Some western retro fans dig into older PC titles, but few examine the history of computer games outside the US and Europe. And that’s a shame, because the Japanese computer gaming scene of the 80s and 90s produced some incredible works, many of which have never seen an official release on other platforms. These games cover unusual themes and subjects, incorporate complex gameplay systems, present aesthetics completely distinct from their console counterparts, and in many ways were far ahead of their time.

An Extremely Brief History of Japanese Personal Computers

Japanese computer systems of the 80s and 90s were different from those we had in the US. While we had Commodores, Macs, and MS-DOS/Windows machines, the Japanese market was dominated by domestic Japanese companies up until the mid-90s. Japanese computer manufacturers and software developers had different considerations to contend with than their Western counterparts. For instance, Japanese machines had to be capable of displaying Kanji characters, a feat that was impossible on IBM machines of the time due to their sheer number and complexity. In addition to the storage issues involved, Kanji simply could not be rendered in the tiny fonts used to display letters in DOS.

Additionally, the language barrier prevented companies like Apple from getting a foothold in the Japanese market. And so, throughout the 80s, the four primary home computing machines were the FM-7, PC-88, MSX, and X1, produced by domestic firms Fujitsu, NEC, ASCII, and Sharp, respectively. Later, these would be succeeded by the FM Towns, PC-98, MSX2, and X68000.

Some of these machines, like the FM Towns, had technical specifications that made them natural platforms for game developers. Others, like the PC-98, were originally designed as business computers but had such a vast install base that developers found ways to work around their limitations by focusing on slower-paced genres like dating sims and turn-based RPGs. Developers for these systems ranged from well-known names like Konami, who launched the Metal Gear series on the MSX2, to software companies dabbling in the increasingly-lucrative computer gaming market, to individual hobbyist or “doujin” creators.

Hydlide

Complex Systems

Whereas home consoles like the Famicom and Sega Mk III (known in the US/Europe as the Master System) were attractive for their libraries which were often influenced by arcade-style action games, development for many Japanese home computers tended to focus more on genres less reliant on speed and precision, as these machines were not built with games in mind. Of course, there were exceptions — machines like the FM Towns and Sharp X68000 were so powerful and similar to arcade boards that they could run ports of titles like Street Fighter 2, Splatterhouse, and Turbo Outrun more faithfully than even 16-bit home consoles. But when porting arcade titles was difficult or impossible, developers came up with unusual and even groundbreaking concepts and mechanics.

Japanese personal computers spawned three huge, well-regarded RPG series in the 1980s: Hydlide, Dragon Slayer, and Mugen no Shinzou. These titles drew inspiration from arcade fantasy action games like Tower of Druaga as well as western computer RPGs like Ultima and Wizardry, effectively launching the action RPG and JRPG genres and laying the groundwork for globally successful console-based series such as The Legend of Zelda and Dragon Quest.

Relics

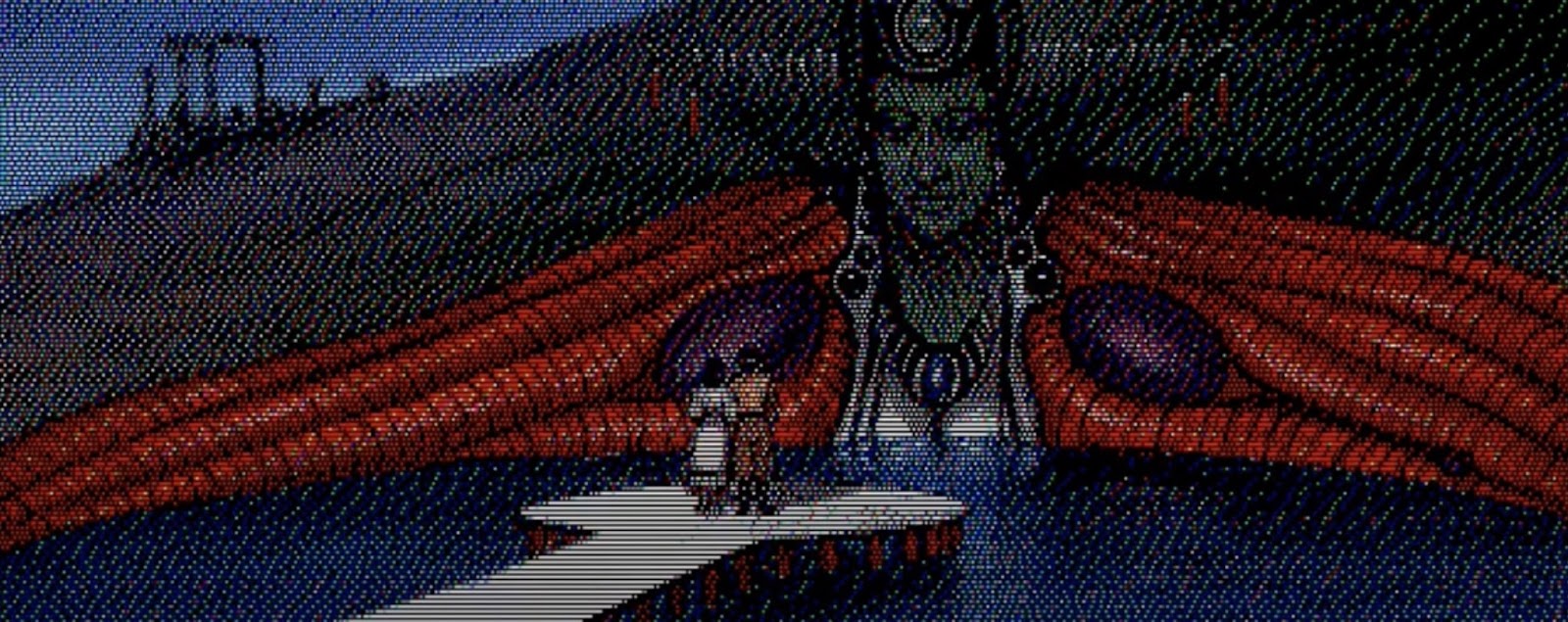

But there are many lesser-known Japanese PC titles that explored unique mechanics and gameplay systems, as well. Relics, released in 1986 for the PC-98, is a side-scrolling adventure game that takes heavy visual inspiration from the works of H.R. Giger. The game is wildly ambitious for the time, giving players the ability to possess nearly any of the creatures they find while exploring an immense tower, from animals to humanoid soldiers.

Each creature has different abilities and powers, and the lack of direction provided aside from notes found throughout the game anticipates the open-ended and mysterious worlds of games like Metroid and, much later, From Software’s Souls series. Similar to the latter, the player’s choices throughout Relics can change hidden global values which trigger one of three different endings. It’s far from a perfect game — the PC-98’s limitations mean that there’s significant slowdown, for example — but it’s a unique take on the adventure genre that spawned several sequels, most of which remain relatively unknown outside of Japan.

Even in cases where Japanese PC games and genres were ported to home consoles, their systems and themes were often simplified to cater to younger audiences and the more limited input methods of the time. Take the SNES game E.V.O.: The Search for Eden — a side-scrolling action game with some RPG elements in which the player uses experience to evolve from a tiny, pathetic fish into a giant sea monster, then an amphibian, a reptile, and so on.

46 Okunen Monogatari: The Shinkaron

That title was actually adapted from Almanic’s 1990 PC-98 game 46 Okunen Monogatari: The Shinkaron, which is instead a turn-based RPG. While the combat is simplistic and comparable to console RPGs of the time, the evolution system is much more complex than in E.V.O. Rather than just buying body parts, here players spend points to upgrade different abilities. When one is maxed out, you evolve into a new form and can then further evolve, sometimes into a form that causes a premature ending — like you becoming Godzilla and rampaging across the planet. And whereas E.V.O. ends with you perhaps becoming a mammal, 46 Okunen Monogatari: The Shinkaron takes you into an anime-esque future with demons, lizard people, and elves who have to defeat Lucifer, a sexy blonde lady from the moon who is also a giant spider monster.

Digan no Maseki

Digan no Maseki, on the PC-88, PC-98, and MSX2, is another example of an RPG with complex systems for its time, including some that anticipate the widespread “survival” mechanics of many modern indie games. Whereas eating and sleeping were typically voluntary actions in most early console RPGs that restored player character health or allowed saving the game, in Digan no Maseki players must not only eat and sleep at regular intervals but can even catch illnesses, from colds to sexually transmitted infections.

Distinctive Styles

Decades after the NES, Super Nintendo, and Sega Genesis, “8-bit” and “16-bit” aesthetics have become codified in many players’ minds. Modern releases continue to trade on the recognition of these aesthetics, even when they don’t necessarily stick to the precise technical and graphical limitations of the games they’re attempting to evoke. Games developed for platforms like the NES and SNES tended to look similar to one another for a variety of reasons, including prevailing artistic conventions, restrictions on sprite size and on-screen colors, and the ability or inability of hardware to perform functions like sprite rotation and parallax scrolling. The Japanese home computers of the 80s and 90s had completely different architectures, meaning that many of the games produced for these systems have very distinctive looks when compared to their console counterparts.

YU-NO: A Girl Who Chants Love at the Bound of This World

PC-98 games, for instance, tend to have a very detailed, anime-inspired visual style. There are three main reasons for this: first, the difficulty in producing high-speed action games for the machine meant that creating eye-catching characters and UI elements became more of a strategy to entice potential players. Second, the PC-98’s display was a relatively high resolution of 640×480, allowing for detailed illustration work. Finally, the hardware could only render 16 colors at a time. This meant that artists working with the machine needed a keen sense of color theory, and also led to the widespread use of dithering to create different effects. The result is the fine-lined, high-resolution art of large characters and scenes that has had a profound impact on vaporwave and other retro-focused aesthetic movements.

CRW: Metal Jacket

CRW: Metal Jacket is an iconic example — much of the visual field is taken up by elaborately detailed UI elements, which means that the actual moment-to-moment gameplay action occupies only a portion of the display. You can see the use of dithering in the anime-style character portraits, where it’s employed to create complex shadows and gradations.

Of course, not all games on Japanese computers had anime-inspired aesthetics. One example of a title with a vastly different style is the aforementioned Digan no Maseki. The game filters the distinct biomechanical art of Naoyuki Kato through the graphical limitations of PC hardware, achieving a wonderfully detailed look that was unlike anything else at the time.

Adult Themes

Even in Japan, console producers like Nintendo and Sega had licensing procedures restricting the kinds of software they would allow to be published for their hardware throughout the 1980s and 1990s. And while standards were somewhat less strict than Nintendo of America’s famously tough content policies barring religious imagery, sexuality, excessive violence, and so on, there were still limits. Additionally, independent developers and hobbyists typically couldn’t afford to go through the licensing and cartridge acquisition process, instead creating games for PCs. That meant that the range of content in PC games was far broader than that available on consoles like the Famicom. And yes, this meant that much like today’s Steam ecosystem, there were a lot — a lot — of hentai games for Japanese personal computers.

Last Armageddon

That’s not to say that these were all straightforward titillation. YU-NO: A Girl Who Chants Love at the Bound of This World is an eroge (erotic game) released in 1996 for the PC-98 and contains panty shots, full-on penetration, and even incest references. But it’s also far from an attempt to make a quick buck off perverts, featuring a complex time travel storyline and gameplay system that allows the player to travel through parallel worlds to explore different routes. As a result, YU-NO had a major impact on visual novels, and was later ported to the Sega Saturn and Windows with the sexual content removed.

But there are other “adult” themes beyond sexuality that made their way into Japanese PC games at a time when consoles wouldn’t touch them. Telenet’s XZR, released in 1988 for the PC-8801, MSX2, and PC-9801, casts the player as a Syrian Assassin named Sadler in a narrative involving violence and intrigue and eventually culminating in the protagonist traveling into the future to assassinate both the President of the United States and the General Secretary of the Soviet Union. Additionally, Sadler can take drugs like hash, LSD, and opiates, all of which have both beneficial and detrimental effects, and can cause death if overused. Needless to say, it was never ported to home consoles — only its sequel was, and the North American version for the Genesis saw a number of content edits to make it more acceptable to the western market at the time.

XZR

Retro Japanese PC Games Today

The difficulties for contemporary western audiences interested in retro Japanese computer games are twofold. There’s the language barrier, of course, but there’s also the difficulty in actually getting these games to run on modern hardware. Thankfully, dedicated preservationists and translators have made these issues less and less problematic. Groups like 46 OkuMen have translated games such as 46 Okunen Monogatari: The Shinkaron, Rusty, and CRW: Metal Jacket. Emulators such as Neko Project II, blueMSX, and Tsugaru now exist. There are even ports of games like Relics and Hydlide to modern consoles like the Nintendo Switch available, with limited translations. And while PC emulation can be more challenging to set up than console emulation, it’s certainly possible to play many Japanese PC games from the 80s and 90s on Windows, Mac, and Linux machines today.

And more people should! From a historical standpoint, it’s fascinating to explore the different approaches that programmers and artists took to development for Japanese PCs versus the consoles of the time. But even beyond this academic interest, many of these games offer mechanics, visual styles, and narratives that are still unique today. The libraries of the PC-98, MSX, FM Towns, and other Japanese computers of the 80s and 90s deserve wider recognition amongst western audiences and appreciators of retro games, and hopefully the increased efforts to emulate and translate some of these titles will contribute to a long-overdue broadening of the retro canon.

Great stuff Merritt!