For a significant portion of my life, I was not able to discuss games critically or casually without someone bringing up “ludonarrative disonance.”

“Ludonarrative disonance” is an academic term, brought over from game studies, or ‘ludology.’ “Ludus” here is the latin root for “to play;” ‘ludology’ is the study of games; ‘ludonarrative’ is the story of a game; ‘ludonarrative disonance’ is the distance between a player’s actions and story, the distance between the game as the player Plays it and the game as the game Tells itself. As a piece of craft, I hate this term, and I think its escape out of academia and into broader criticism has been a disaster. The problem of “ludonarrative disonance” is that games are not narratives, they are toys. The purpose of a game is to be played.

The problem with framing games as toys is that games criticism is maddeningly self-conscious. In 2005, film critic Roger Ebert declared that video games were not art, and it feels like everything in the field— from criticism to development— has been in reaction to that statement. Tragically, instead of building an argument for why play is itself art, “games” as a culture has reacted by shaping video games in the image of pre-existing narrative forms. The field has become all narrative and no ludo. This choice is reflected in what kinds of games get made, what kinds of games get critical attention, and the visual structure and design of games themselves.

The Last of Us (2013, Naughty Dog) is the best case study of this form of game— a game that received great acclaim and attention, but has contributed relatively little to games as a medium. Most of the acclaim and discussion around The Last of Us (Naughty Dog) focuses on its narrative, but relatively little focuses in on the gameplay. Gameplay is from a third-person perspective, and the player spends most of their time managing their inventory and their hostile environment, minimizing sound that may make them a target and handling any hostile characters that the player may encounter. The central mechanics of The Last of Us (Naughty Dog) can be described without mentioning the narrative at all, which makes its adaptation in The Last of Us (HBO) feel not only natural but inevitable.

Does it count, to read the synopsis on Wikipedia instead of watching the film yourself? What about if you read the novelization of a movie? Or is there something essential to the medium itself, something that is experienced only in watching the film? Transferring the “narative” out of a game, and by more or less seamlessly replicating an already told story into an entirely different medium, is a tacit admission that the gameplay is not necesscary to experiencing the ‘narrative.’ When people talk about the The Last of Us (Naughty Dog), are they talking about gameplay, or are they talking about details that would seamlessly melt into The Last of Us (HBO)? If the narrative of a game is not explicitly expressed within the mechanics, I do wonder why the work has to be a game at all.

Framing The Last of Us as being narratively innovative is particularly frustrating given that it shares so much thematically with the 1956 western The Searchers. In The Last of Us, the main character, Joel, loses his daughter in the first act; she is shot to death by a soldier in the escalation of the end of the world. His motivation and actions as a character are all read downstream of that loss. His devotion to Ellie (the secondary protagonist) is devotion to a surrogate of his daughter. Joel’s embrace of violence is a paradoxical attempt to reclaim innocence, his daughter’s and the world’s before a plague that made people into subhuman, violent creatures. Ultimately, Joel is unable to hold onto his surrogate daughter— in refusing to allow another faction to kill her to develop a vaccine from her tissues, he saves her life but damns the world. She cannot forgive him for it.

The Searchers is about a former Confederate soldier whose family and world is destroyed when his brother’s West Texas settlement is raided by the Comanche and his neice is kidnapped. The main character, Ethan Edwards, becomes ever more violent in his relentless pursuit of his neice over a period of years. Eventually, he finds her, alive, and delivers her back to her family and back to white society. The movie closes with Ethan unable to join the reunion—- the violent thing he has become to nominally save his neice prevents him from rejoining the world with her.

These stories are not precisely the same, but they do rhyme in an odd way. No work exists in a vacuum: it is not uncommon for iconic works to be adapted, co-opted, or incorporated into works that come after them. The problem of The Last of Us and its similarities to The Searchers is that The Last of Us is framed as an innovation and a high-water mark in the maturity of games as a form. All Naughty Dog had to do to get games taken seriously was make a game whose gameplay was completely superfluous to a story that had already received wide acclaim and respect when it was a movie.

Further, nothing that the player does in The Last of Us matters—- that is, there is no choice to be made in gameplay that has an affect on narrative. This railroading makes it much easier to adapt the game to television (the narrative is entirely linear!); it also makes the actual gameplay wholly superfluous. Everything that happens in The Last of Us leads to one ending, to one action about one relationship. Ellie’s response to Joel’s choices are maddening as a player; in embodying Joel throughout the runtime, the player has been on rails. There is no alternative, and then other characters in the narrative condemn the player for “making” those choices. The game itself gets mad at you for engaging in it— see also: Braid (2008). If this is complexity or maturity— if this is where ludonarrative dissonance leads the medium— I think it may be a dead end.

Beyond narrative, high profile, big-budget triple-A games have adopted and popularized visual design that feels like a total abdication of potential. The Last of Us (Naughty Dog) is entirely animated— every piece of visual information in that game is designed and created by an artist: there is not a warehouse somewhere with a box that contains the exact gun that Joel used to shoot Marlene. Why does it look the way it does, then? Most games are animated. A vanishingly small number of them use actual footage of actual actors (and these are usually 20+ years old at this point) and some are animated using physical sculpture (such as claymation).

With the current state of technology, computers and game consoles have an unprecedented ability to generate and show the look of a world. These advances are usually referred to as “graphics”— “This game has good graphics,” or “I’m not impressed by the graphics.” Graphics usually denotes a capacity for realism, to use powerful sheets of individual polygons to capture the nuance of every leaf on a tree, to perfectly replicate the shape and texture of a stone building, to render human faces that look human.

For many years, this realism was an impossible dream, something to be sought after at all costs and forever out of reach. Within my lifetime, however, rendering a realistic face has become more than possible— it has become the mainstream in filmmaking and games alike. Some of this has been exacerbated by the advances in rotoscoping, an animation technique in which figures and sequences are animated directly over live footage of actual actors. Rotoscoping has advanced into motion capture, a similar technique which captures more data and three-dimensional data. Game characters are no longer designed or drawn, they are acted, often by actors players would recognize from movies or TV.

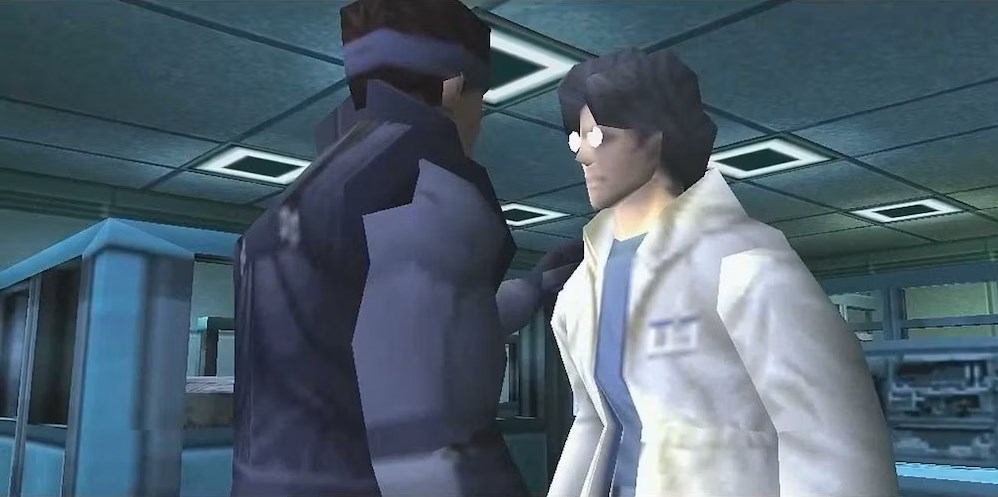

The first Metal Gear game was published in 1987 and new ones (and remasters) have been published periodically since. Early Metal Gear is thus a reflection of the technical limits of early gaming; late Metal Gear is a reflection of advances. A visual transition that fascinates me is the shift from Metal Gear Solid (1998) to Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain (2015). Metal Gear Solid is rendered in large, simple polygons; making a physical model of Snake from that game would require one sheet of paper and a few pieces of tape. Faces are rendered impressionistically, simple and often blurred. There is often no animation of individual facial features; instead the whole figure moves. By contrast, Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain features extensive motion capture and rotoscoping, such that the main character (Snake) was recast not only vocally— Keifer Sutherland taking over for David Hayter— but visually, with Snake’s model developed from motion-capture data from Sutherland’s performance. Metal Gear Solid was presented with the limits of hardware and software in 1998 and turned to art direction to expressively fill the gaps. Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain was provided an eye-watering budget and unbelievably advances in technology and rendered realism. This is a move that is less expressive and less interesting.

The transition out of “art direction” and into “graphics” is generally framed as a great gain for the medium, but I know what the “real world” looks like; I live there. I know what Kiefer Sutherland looks like, and I don’t particularly relate to him. In the indistinct, pixelated features of Metal Gear Solid (1998), there is more to interpreted. There are gaps that the player can position the self in.

Of course, strong art direction and visual design in a game goes beyond making an appealing player character. Katamari Damacy is one of the most best looking games ever made. The original game is twenty years old, made in 2004 for the PlayStation 2 and within those technical limits. Katamari Damacy‘s world is populated with simple, polygonal models with hard edges. The animations are simple, with most figures operating with one or two points of articulation, and most of the figures are rendered in solid colors without gradients or shadows. The game looks so good, still, with its simple models and design. Katamari Damacy is not a game with “graphics” but it is certainly a game with art direction.

Katamari Damacy is also impossible to describe without discussing its mechanics. Ludo: the player has a big ball that they roll around an item-stuffed environment, picking up objects smaller than the ball, ideally to hit a specific circumference within a time limit. Narrative: the King of the Cosmos has destroyed or misplaced the bodies of the heavens, and he needs his son to go make some new ones by rolling up objects with a large ball. The two are intertwined, and the narrative is itself subsumed by the mechanic. What would an adaptation of Katamari Damacy without play even look like?

Katamari Damacy is much more obviously a toy; it is a game that looks like a toy and a game that is focused on gameplay experience. The toy comparison is also much more natural given that its story is silly and the world is, too. More serious games, however, are also capable of operating with gameplay and art direction. Papers, Please (2013) is a game in which the player is an immigration officer in a fictional dictatorship. The gameplay is about examining various kinds of immigration papers and either letting NPCs through or keeping them inside the country. Additionally, the player must manage their meager finances. The game is, essentially, all gameplay. Every intereaction presents the user with a choice, and all of those choices are impactful on the rest of the game’s systems. Refusing to detain a person with inadequate paperwork or holding contraband will result in increased scrutiny from superiors and less pay; going into debt results in a game over. The game also uses pixel art, with figures and environments and objects more obviously “drawn” rather than “rendered.” There’s a real, artistic ethos to Papers, Please. Although the dystopian setting is only directly experienced within the boundaries of the checkpoint office, every NPC expresses the environment they come from via the heavy shadows on their pixel-art faces and the limited, muddy color palate. Is this less mature for being play oriented, or for eschewing expensive, elaborate “graphics?”

It feels like there has been a flattening in what games can be and what games can do, and this is ironic given that the technology to make them has never been more advanced or accessible and that independent distribution for games is more available than it ever has been. Developing a game no longer requires prohibitively expensive or hard-to-find equipment, and players are no longer limited to what GameStop deigns to carry. Despite this, mainstream gaming, triple-A gaming broadly feels like crude rehashes of the same stories with great “graphics” that amount to dull tech-demos. There is so much potential in games, potential in what only games can do.

One of my favorite games— and one of the few that Roger Ebert himself praised— is Cosmology of Kyoto (1993). The game takes place one night in Heian era Kyoto, around the year 1000. The player wakes as a naked person and must take their clothes from their last corpse. There is no set objective, just a scrupulous simulation of medieval Kyoto for the player to explore and inhabit. Kyoto is, of course, populated by commoners and beggars and noblemen, but also demons and ghosts and priests. The player is able to explore and embody medieval Japanese religious philosophy and thought— it is not uncommon to die several times in a playthrough and experiences Buddhist hells (or to have foul enough karma that you are reincarnated as a dog). One of the most interesting parts of the game is an accurately appointed Buddhist altar, featuring a number of tools utilized in prayer. If the player interacts with these tools in the correct order, they are briefly given a glimpse of nirvana.

This is not the same as reading a book about Japanese Buddhist practice or belief, and it is not the same as watching a monk pray. This is using games as a medium to let the player embody a set of beliefs and their consequences, despite millennia of separation. It does not matter whether or not the player believes in these things; the character they are playing does, and the distance between those two things allows for the player to experience something truly novel. But the graphics aren’t impressive and you couldn’t shop it to HBO for adaptation, so does it even really count as a game worth playing?

3 Comments